31 Aug 23 - Activity: Frames and Coordinates#

Forces in different frames#

One of the critical things that we must note is that the natural world changes and we observe it. The models (or laws) that we use to describe nature must accurately describe our observations. This is challenging when observers use different frames (or even different coordinates in the same frame) to show we have the same observations. Moving between coordinate systems and frames is a critical skill in physics.

Polar coordinates#

Many problems in physics require the use of non-Cartesian coordinates, such as the Hydrogen atom or the two-body problem. One such coordinate system is plane-polar coordinates. In this coordinate system, any vector \(\mathbf{r}\in \mathbb{R}^2\) is described by a distance \(r\) and angle \(\phi\) instead of Cartesian coordinates \(x\) and \(y\). The following four equations show how points transform in these coordinate systems.

Getting Oriented#

✅ Do this

Borrowed from CU Boulder Physics

A particle moves in the plane. We could describe its motion in two different ways:

CARTESIAN: I tell you \(x(t)\) and \(y(t)\).

POLAR: I tell you \(r(t)\) and \(\phi(t)\). (Here \(r(t)\) = \(|\mathbf{r}(t)|\), it’s the “distance to the origin”)

(a) Draw a picture showing the location of the point at some arbitrary time, labeling \(x, y, r, \phi\) and also showing the unit vectors \(\hat{x}, \hat{y}, \hat{r},\) and \(\hat{\phi}\), all at this one time.

(b) Using this picture, determine the formula for \(\hat{r}(t)\) in terms of the Cartesian unit vectors. You answer should contain \(\phi(t)\).

(c) Write down the analogous expression for \(\hat{\phi}(t)\).

(d) We can claim the position vector in Cartesian coordinates is \(\vec{r}(t) = x(t)\hat{x} + y(t)\hat{y}\). Do you agree? Is this consistent with your picture above?

(e) We can claim the position vector in polar coordinates is just \(\vec{r}(t) = r(t)\hat{r}\). Again, do you agree? Why isn’t there a \(+\phi(t)\hat{\phi}\) term?

Getting Kinetic#

✅ Do this

(a) Now let’s find the velocity, \(\vec{v}(t) = d\vec{r}/dt\). In Cartesian coordinates, it’s just \(\vec{v}(t) = \dot{x}(t)\hat{x} + \dot{y}(t)\hat{y}\). Explain why, in polar coordinates, the velocity can be written as \(d\vec{r}/dt = r(t)\:d\hat{r}/dt + dr(t)/dt\:\hat{r}\).

(b) It appears we need to figure out what \(d\hat{r}/dt\) is. Use the formula your determined in question 1b to get started – first in terms of \(\hat{x}\) and \(\hat{y}\), and then converting to pure polar.

(c) Write an expression for \(\vec{v}(t)\) in polar coordinates.

(d) Finally, determine the acceleration \(\vec{a} = d\vec{v}(t)/dt\). In Cartesian coordinates, it’s just \(\vec{a}(t) = \ddot{x(t)}\hat{x} + \ddot{y}(t)\hat{y}\). Work it on in polar coordinates.

Forces and acceleration in plane-polar coordinates#

We can show that the acceleration in plane-polar coordinates is given by:

Because this coordinate system is orthgonal (\(\hat{r}\cdot\hat{\phi} = 0\)), we can write the Newton’s second law in this coordinate system as:

So that,

and

Example to Work in a Group#

✅ Do this

Borrowed from Taylor’s Classical Mechanics

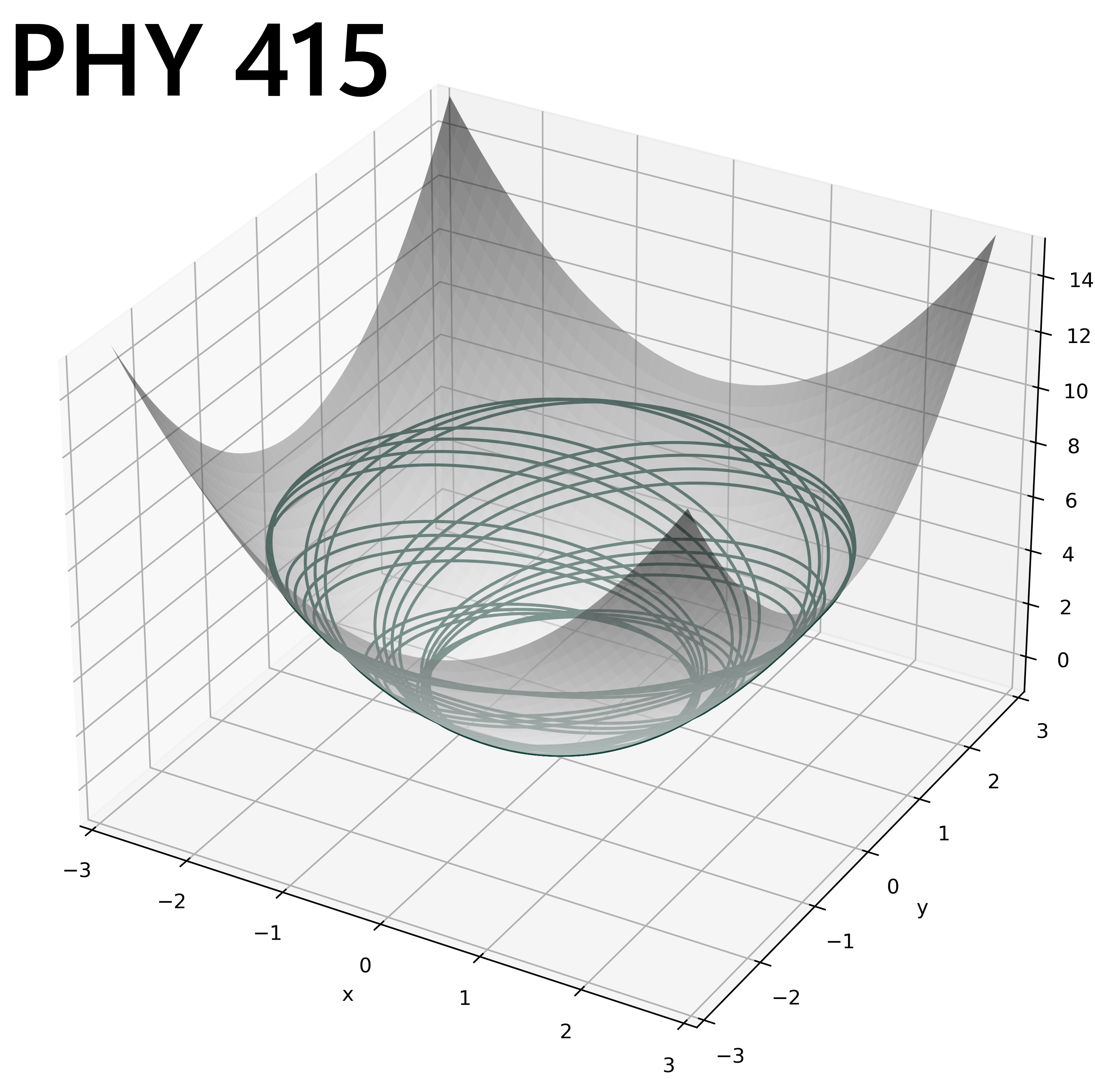

Consider a “half-pipe” that has a circular cross section of radius \(R\). If we release the skateboard near the bottom of the “half-pipe” approximately how long does it take to get to the bottom?

Make sure you draw a picture and define your coordinate system.

Consider all the assumptions you need to make to solve this problem, and write them down.

Be careful not to make big assumptions too early; try instead to write the forces acting on the skateboard in plane-polar coordinates.

Do not use Lagrangian dynamics to solve this problem if you know how you, please instead use Newton’s Second Law.

Hint: The equation of motion to small angle oscillation frequency pipeline is real.