Homework 9 (Due November 1st)

Homework 9 helps you further investigates the multipole expansion and develop models for polarization that we will use to understand electric fields in matter. Notice that for polarization problems, we can often find the bound charges and solve the problems much like we have done before with free charges.

Dropbox file request for Homework 9

1. The Beauty of the Multipole expansion

The multipole expansion is a very powerful approximation that arises in a number of different kinds of field theories. The beauty of it is that it can provide a simple approximate form for the field in question far from the sources that produce the field. Often, this is helpful when solving problems where you only care about the dominant contributions because the others only provide small corrections to the behavior.

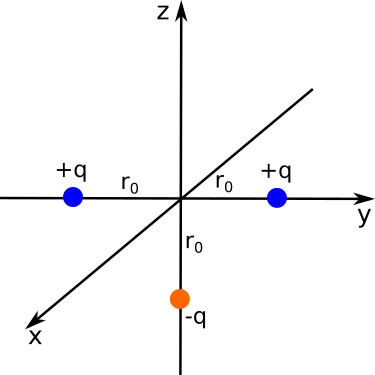

In this problem, you will explore the the multipole expansion for the charge configuration shown below.

- For the three charges shown above, determine the approximate potential at a distance far from the origin of coordinates. Keep only the two lowest non-vanishing orders of the expansion. Notice that each is a distance $r_0$ from the origin.

- Explain how you know the two terms you find are the lowest non-vanishing terms for the potential.

- Using your answer to part 1, find the approximate electric field produced by this system of charges far from the origin. Express your answer in spherical coordinates.

2. Multipole Expansion of a Single Point Charge

For this problem, consider a single point charge $+q$.

- Place the charge at the origin, write down the electric potential at a location $\mathbf{r} = \langle x,y,z \rangle$ from the origin.

- Move the charge to a short distance away from the origin on the $z$-axis, $\mathbf{r}’ = \langle 0,0,d\rangle$. Write down the electric potential at a location $\mathbf{r} = \langle x,y,z \rangle$ from the origin.

- Assume the location of interest in Part 2 is far from the charge ($r»d$). Expand your result in Part 2 keeping only the two leading order terms. Interpret these terms in light of the multipole expansion. Hint: It might help to rewrite your result in spherical coordinates.

- How do you resolve that your answer to Part 1 only contains a monopole term where your answer to Part 3 contains additional terms? Explain your reasoning.

3. A Curious Sphere of Charge

In this problem, we ask you to plot a few functions. You have plotted quite a bit using Jupyter, so we expect that you will use a Jupyter notebook of your own design to do your plotting now.

Consider a sphere of radius $R$ that has a volume charge density inside the sphere given by:

\[\rho(r,\theta) = \mu r \sin\left(\dfrac{3\theta}{2}\right)\]where $\mu$ is known constant and $\theta$ is the usual polar angle in spherical coordinates.

- Plot $\rho(r,\theta)/r$ in units of $\mu$ as a function of $\theta$. Where does this charge live in space? Note that $\rho \propto r$.

- Calculate the total charge, $Q$, on the sphere.

- Calculate the dipole moment, $\mathbf{p}$, of the sphere.

- Use your results from Parts 2 and 3 to find $V(r,\theta)$ when you are far from the sphere ($r»R$). Discuss how your results make sense with the plot in Part 1.

- The function $\sin\left(\frac{3\theta}{2}\right) \approx \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} + \frac{3}{2\sqrt{2}}\cos\theta$, which would suggest that the volume charge density can be written as $\rho(r,\theta) \approx \frac{\mu r}{\sqrt{2}} + \frac{3\mu r}{2\sqrt{2}} \cos \theta$. So this will look like a superposition of a spherically symmetric density and a density proportional to $\cos \theta$. Plot $\rho(r,\theta)/r$ in units of $\mu$ as a function of $\theta$ in this approximation.

- How does your plot in Part 1 compare to your plot in Part 5? Is this a good approximation to the original charge density? What does this imply about our approximation of $V$ compared to the exact $V$?

4. Atomic hydrogen and the polarization model

Griffiths Table 4.1 gives an experimental value for $\alpha/4\pi\varepsilon_0$ for atomic hydrogen. (Read his caption carefully for units!)

- The “atomic polarizibility”, $\alpha$ is defined by $\mathbf{p}=\alpha\mathbf{E}$. Study Griffiths’ Example 4.1, which tells you how to estimate the atomic polarizability, summarize the example in your own words.

- Following the example and using it with this experimental value for $\alpha/4\pi\varepsilon_0$ for atomic hydrogen, estimate the atomic radius of hydrogen. How well did you do, compared, say, with the Bohr radius?

- After summarizing the example, tell us what physical assumption (simplification!) Griffiths is making about the physical distribution of negative charge inside an atom? Is that realistic?

- Now suppose you have a single hydrogen atom inside a charged parallel-plate capacitor, with plate spacing 1 mm, and voltage 100 V. Determine the “separation distance” $d$ (as defined in that same Example 4.1 problem) of the electron cloud and the proton nucleus. What fraction of the atomic radius of part 2 is this? (You should conclude that 100 V across a 1mm gap capacitor is unlikely to ionize a hydrogen atom, do you agree?)

- Use your calculations to roughly estimate what voltage (and thus, what E-field) would ionize this single hydrogen atom. (We’d say if you can pull the electron cloud one full atomic radius away, it’s breaking down! )

5. Polarized sphere of charge

Consider a dielectric sphere of radius $a$ that has a polarization that is directed radially outward from the center of the sphere, $\mathbf{P} = P_0\mathbf{r}$.

- Determine the bound charges at the surface, $\sigma_B$, and in the volume of the sphere, $\rho_B$.

- Find the electric field everywhere.

- Sketch the electric field lines inside and outside the sphere. What does your sketch say about the electric field at the boundary of the sphere? Does this make sense to you? Why or why not?

6. Charge conservation

When a neutral dielectric is polarized, no new charges are created or destroyed, so the total charge must still be zero. The charge density on the surface is given by:

\[\sigma_B = \mathbf{P}\cdot\hat{n}\]The charge density in the bulk is given by:

\[\rho_B = -\nabla \cdot \mathbf{P}\]Using these definitions, show that the total charge for any neutral dielectric with a polarization $\mathbf{P}$ is zero.