Homework 6 (Due October 11th)

Homework 6 emphasizes the conductor problem, which requires new methods to approach finding $V$ or $\mathbf{E}$ as we are often unable to find $\rho$ a priori. In the presense of an external electric field, charges will shift in a conductor, thus complicating matters of finding $\rho$. We start with a computational problem that harkens back to energy and energy density to unpack a little puzzle we discussed in class.

Dropbox file request link for Homework 6

1. Another Energy Puzzle

In class, we discussed how the total electrostatic energy of two point charges will change as they are brought together. The result felt somewhat counter-intutitive. For two point charges of opposite sign, the total energy decreases as we bring them together. In this problem, you will explore this situtation computationally. You can download the notebook (or view it here).

- In the jupyter notebook, we have created two point charges whose field we can see in 2D space. For this problem, we will limit our solution to the plane to reduce computational load. It looks like the dipole that we have seen before. The algorithm you will develop to determine the approximate total energy relies on the energy density: $u(\mathbf{r}) = \frac{\varepsilon_0}{2}E(\mathbf{r})^2$. Compute the energy density at each point in the space and plot the result in 3D (with the 3rd dimension representing the energy density at each point). Here, you might need to look into making surface plots or contour plots in Python (your choice). Comment on any features of the energy density that you notice.

- Now, pick a point between the two charges (maybe the midpoint), and plot the energy density at that point vs separation between charges. What do you notice a how the local energy density changes as the charges get closer together?

- Add up the density at every point in space to find the estimated total energy $U \approx U_{est} = \sum u_i(\mathbf{r}_i)$.

- Now, that you have tools to compute the energy density in 2D space from part 3, recompute it for different values of the separation between the charges, and plot the results ($U_{est}$ vs $r_{sep}$). What happens to the estimated total energy as the charges get closer together?

- Given what you have learned from parts 4 and 6, what is the story regarding energy density and total energy as the charges move closer together?

- BONUS - We have made a choice of mesh (number of grid points) and total space (how big the space is). How good were those choices? That is numerical solutions are always estimates. We seek convergence to some solution that is numerical in nature, so how good did we do?

2. Capacitors, metals, and continuity

We have discovered that there is a curious result when looking at the electric field across a boundary. It is discontinuous! by an amount that is consistently the same expression ($\sigma/\varepsilon_0$). However, we have also found that the electric potential across the boundary is continuous.

Consider a very large set of metal capacitor plates separated by a small distance $d$. Each plate is charged with an equal amount of charge, but the left plate is negative. So, the left plate carries $-\sigma$ and the right plate carries $+\sigma$.

- Find the electric field everywhere in space (consider that the plates extend to infinity to ignore any edge effects).

- Plot the component of the electric field along a line that runs to the plates.

- Find the electric potential everywhere in space. You are free to set where $V=0$, but be careful when doing so as the distribution of charge extends to infinity!

- Plot the electric potential along the same line as in Part 2.

- What do you notice about the graphs you sketched in Parts 2 and 4?

- BONUS: Consider that the plates have some depth to them (as with any real physical plate). Let them have a width $w$. Using what you remember or know about metals, what happens to your graphs in Parts 2 and 4? (For example, we will learn soon that metals in electrostatics are equipotential surfaces.)

3. Gauss’ Law and Cavities

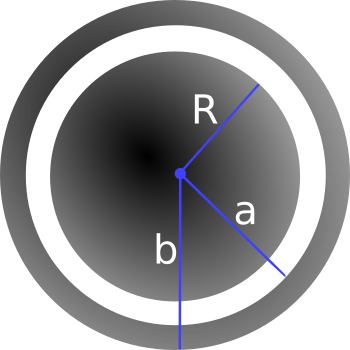

A metal sphere of radius $R$, carrying a charge $+q$, is surrounded by a thick concentric metal shell (inner radius $a$, outer radius $b$). The shell carries no net charge. Where requested, please explain your reasoning.

- Sketch the charge distribution everywhere. If the charge is zero anywhere, indicate that explicitly.

- From part 1, you probably noticed the charge distributes in some way on the metals. Determine the surface charge density $\sigma$ at $R$, at $a$, and at $b$.

- Sketch the electric field everywhere; explain how you know the field you have drawn is correct. If the field is zero anywhere, indicate that explicitly.

- Find the potential everywhere, use $r \rightarrow \infty$ as your reference point for $V=0$.

- Now the outer surface is touched by a grounding wire, which lowers its potential to zero. How do your answers change to parts 2 and 4? Explain your reasoning.

4. Coax capacitors

Consider a coaxial cable with an inner conducting cylinder has radius $a$ and the outer conducting cylindrical shell has inner radius $b$. It is physically easy to set up any fixed potential difference $\Delta V$ between the inner and outer conductors. In practice, the cable is always electrically neutral.

- Assuming charge per length $+\lambda$ and $-\lambda$ on the inner and outer cylinders, derive a formula for the voltage difference $\Delta V$ between the cylinders.

- Assuming infinitely long cylinders, find the energy stored per length (W/L) inside this capacitor. Notice we are asking for the energy per unit length, the answer is not infinity! Let’s do it two ways so we can check:

- Find the capacitance per length ($C/L$) of this system, and then use stored energy $W = \frac{1}{2} C (\Delta V)^2$.

- Integrate the energy density stored in the E field.

- Based on your answers to part 2, where in space would you say this energy is physically stored?

- Estimate the capacitance per meter of the coaxial cable that the cable company uses to send TV signals into homes. Justify any assumptions.

- This model is also excellent for “axons”, which are long cylindrical cells (basically coax cables) carrying nerve impulses in your body and brain. Estimate the capacitance (in SI metric units, Farads) of your sciatic nerve. Assumptions - the sciatic nerve is the longest in your body, it has a diameter of roughly 1 micron, and a length of perhaps 1 m. Note that axons generally have a value of b which is very close to a (i.e. the gap is extremely tiny, b-a is about 1 nanometer. ) so you can simplify your expression using $ln(1+\epsilon)\approx\epsilon$.

5. What is a farad?

- The farad is actually an enormous unit of capacitance. To illustrate this, treat the Earth as a conducting sphere and find its capacitance.

- Look up the capacitance of typical capacitors used in electronic applications. If these capacitors were conducting spheres, roughly how large would they be physically? Does this size seem to be the right size given your experience with electronic components?

6. Superposition in conductors (“shielding”)

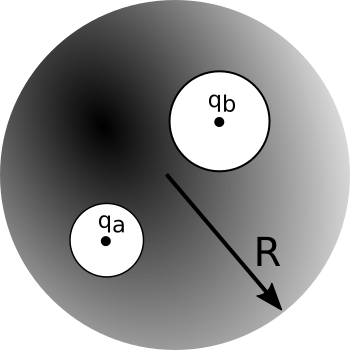

We carve out two spherical cavities from a metal sphere of radius $R$ (as shown below). The first cavity (radius, $a$) has a charge $+q_a$ placed at the center of the cavity. Similarly, the second cavity (radius, $b$) has a charge $+q_b$ placed at the center of that cavity.

- Sketch the surface charge everywhere. Explain how you know the surface charge looks this way.

- Determine the surface charges ($\sigma_a$, $\sigma_b$, and $\sigma_R$).

- Sketch the electric field everywhere. If the field is zero anywhere, indicate this explicitly. Explain how you know the electric field looks this way.

- Determine the magnitude of electric field outside the conductor and inside each cavity.

- If we brought an external charge $q_c$ near the conducting sphere how do your answers to parts 1-4 change? You may answer in words, pictures or both.

7. Proving Uniqueness

For this homework problem, you will prove the “second uniqueness theorem” yourself, using a slightly different method than what Griffiths does (though you may find some common “pieces” are involved!) It will really help to review/read the section on the second uniqueness theorem as you work through this problem.

Do it like this:

- Green’s Identity is true for ANY choice of T and U, so let the functions T and U in that identity both be the SAME function.

- Specifically, you should set them both equal to $V_3=V_1-V_2$ where $V_1$ and $V_2$ represent different solutions to the same boundary value problem ($\nabla^2 V = 0$ with boundary conditions).

- Then, using Green’s Identity (along with some arguments about what happens at the boundaries, rather like Griffith’s uses in his proof) should let you quickly show that $E_3$, which is defined to be the negative gradient of $V_3$ (as usual), must vanish everywhere throughout the volume. QED.

Work to understand the game. We are checking if there are two different potential functions, $V_1$ and $V_2$, each of which satisfies Laplace’s equation throughout the region we’re considering. You construct (define) $V_3$ to be the difference of these, and you prove that $V_3$ (or in this case, $\mathbf{E}_3$) must vanish everywhere in the region. This means there really is only one unique E-field throughout the region after all! This is another one of those “formal manipulation” problems, giving you a chance to practice with the divergence theorem and think about boundary conditions.